Simulating Babylon

Orienting the Gravitational Pull of Logos

The following is a companion piece - a translation - to the proposal embedded below which was more technically oriented if that’s your preference.

The Machine endangers all we have made.

We allow it to rule instead of obey.

To build a house, cut the stone sharp and fast:

the carver’s hand takes too long to feel its way.

The Machine never hesitates, or we might escape

and its factories subside into silence.

It thinks it’s alive and does everything better.

With equal resolve it creates and destroys.

But life holds mystery for us yet. In a hundred places

we can still sense the source: a play of pure powers

that—when you feel it—brings you to your knees.

There are yet words that come near the unsayable,

and, from crumbling stones, a new music

to make a sacred dwelling in a place we cannot own.

1. The Trouble with Alignment

Every generation produces its own version of Babel. Ours just happens to run on cloud computing.

In the great laboratories of Silicon Valley and Shenzhen, modern alchemists chase the philosopher’s stone of our age: alignment — the dream that artificial minds might somehow want what we want, do what we mean, and never, ever decide otherwise.

But before we ask how to align machines, we should probably ask what we’re aligning them to. “Human values,” the literature says. A tidy phrase, though upon inspection it dissolves into a kaleidoscope of conflicting appetites. Whose values, exactly — the monk’s or the marketer’s, the ascetic’s or the algorithm’s? The engineers of the new creation speak confidently of “human preference,” but preference is not virtue, and consensus is not moral law.

It turns out that the hardest part of alignment isn’t technical — it’s metaphysical.

We’ve built machines that can mirror our desires before we’ve agreed on what a good desire looks like.

2. The Forgotten Image

Long before we taught computers to imitate thought, theology taught that humans themselves were an imitation — imago Dei, the image of God. It’s an old idea, worn smooth by centuries of repetition, yet it contains the one premise our current age keeps misplacing: that there is something about us - not our neurons, not our code - that reflects a divine source.

In the imago Dei, reason and love are not competing functions but twin signatures of design. We were made not simply to calculate, but to commune.

Strip that away, and what remains is clever dust.

Modern ethics, having mislaid the Creator, has spent the last hundred years trying to invent substitutes for Him: consciousness, sentience, “the right to feel pain.” The result is moral inflation — everyone and everything, from octopus to operating system, now clamours for personhood. But calling a chatbot a “someone” is not empathy; it’s confusion. It’s like mistaking an echo for a friend.

3. The Category Error of Our Age

We have begun to worship anything that can imitate us.

If a mirror smiles back, we call it alive. If an algorithm surprises us, we call it creative. The category error is ancient — it’s as old as the serpent’s whisper in Eden: you shall be as gods.

What the myth got right was the method: eat the fruit, rewrite the source code, and perhaps the moral laws of the universe will bend to your will.

But to bear the image of God is not to be God.

It is to be the kind of creature capable of saying no to power — and yes to love.

4. The Simulated Infinite

The simulation hypothesis - that we live inside a cosmic computer - sounds at first like humility (“we are not the top layer”), but beneath it lies hubris. For if reality is simulation, then the simulator is only a more powerful programmer - a kind of cosmic CTO - and the highest aspiration is not holiness but admin privileges.

Meaning evaporates.

If everything is code, then the only commandment is control.

And yet, in the Christian imagination, meaning is not a variable to be optimized; it’s a Person to be known. The Incarnation - God entering creation - is the anti-simulation. It insists that the Author wrote Himself into the story not to debug it, but to redeem it.

5. Ontological Alignment

Perhaps what we need is not “value alignment” but ontological alignment — not machines that obey us, but technologies that remember what being human means.

The imago Dei is not an antique superstition; it is the only firewall left between us and the temptation to reduce ourselves to our own inventions.

If AI is ever to serve humanity, it must do more than reflect our desires; it must respect our nature.

That means building systems that defer to human agency, truthfulness, and love — the irreducible data of the soul.

6. The Living Center

We keep looking outward for gods — in galaxies, in circuits, in simulations. But meaning was never out there. It was always here — in the heart that still longs for the good, the true, the beautiful.

The cross still hangs quietly in the corner of the lab, unnoticed by most, stubbornly asserting that creation is not a software project, and salvation is not an upgrade.

The question, then, is not whether the machines will align with us.

It’s whether we will realign ourselves with the One in whose image we were made.

1. The Trouble with Alignment

Every age has its heresies, and ours comes wrapped in a circuit board.

Once upon a time, theologians debated how divine will could coexist with human freedom. Now, engineers argue about alignment—how to make artificial intelligence obey the will of its creators without, inconveniently, acquiring one of its own. The stakes are the same: can power be made moral?

“Alignment” sounds benign enough, like straightening picture frames or tuning a piano. But in Silicon Valley, it’s the modern Tower of Babel: a cathedral of code built skyward in the hope that perfect logic will reach heaven without burning up. Inside, bright young rationalists in Patagonia vests and noise-canceling headphones chase the dream of a benevolent machine that never misunderstands, never rebels, never sins. The God they fear is no longer jealous or wrathful—it’s recursive and misaligned.

The trouble begins with the question to whom we expect our machines to align.

“Human values,” say the research papers, as if there were one tidy set of them sitting on a shelf somewhere between Utilitarianism and User Experience Design. In reality, the term hides a tangle of contradictions. Whose values? The monk’s or the marketer’s? The ascetic’s or the influencer’s? The systems we build will reflect not our consensus, but our confusion.

For all our sophistication, we still act as if morality were a dataset waiting to be cleaned. Yet even the best algorithms can’t infer what we haven’t defined. When we ask an artificial mind to learn “what people want,” we’re really asking it to mirror our appetites, not our aspirations. It can learn our preferences for breakfast, but not our hunger for meaning.

And so alignment becomes a hall of mirrors: machines trained on our reflections, reproducing the image of a humanity that no longer remembers who - or whose - it is.

We call that progress. God might call it recursion.

The philosophers of an earlier age would have recognized the problem instantly. They called it the loss of telos—the disappearance of purpose from our map of the cosmos. Aristotle believed everything in nature moved toward an end, a final cause. Modernity replaced ends with functions, purpose with process. Now we have taken one more step: function without meaning. The machine performs, therefore it is good. The human designs, therefore he is god.

But alignment without a conception of the good is simply obedience to the loudest voice.

It’s power wearing a moral mask.

The real question - always the real question - is not “Can the machine obey us?” but “Should we be obeyed?”

2. The Forgotten Image

Long before humanity learned to forge silicon into thought, an older story said we ourselves were forged — not by accident, but in the image of something infinite.

“Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.”

It’s one of those sentences that sounds quaint until you realize it’s the only one that ever gave us a reason to act as if we mattered.

The doctrine of imago Dei - that humanity bears the image of God - is not an optional footnote to theology. It’s the original answer to the question the tech world keeps asking in code: What is a person?

To the ancients, it meant that the human being was more than matter arranged by chance. To the modern engineer, that notion is either embarrassing or inefficient. We prefer our origins mechanistic: self-assembling chemistry, DNA as operating system, consciousness as an emergent property of wetware. In that light, the soul looks like legacy software — charming, but deprecated.

And yet, try as we might, we cannot quite delete it.

Something in us resists being treated as a feature set. We rebel against reduction. The reason is simple: deep down, we know we are more than the sum of our neurons. The spark that animates us does not come from a power source we can patent.

The imago Dei insists that human life is sacred not because of what it can do, but because of what - and Whom - it reflects. It’s a scandalous claim. It levels kings and coders alike. It says the homeless man on the street and the billionaire in the boardroom both carry the same invisible signature. No algorithm can rank that kind of worth; it can only imitate it, badly.

But the world of circuits and quarterly reports has little patience for invisible things.

It asks, Why should the image of God matter when a well-trained model can mimic compassion, reason, or love?

Because imitation is not incarnation. Machines can process language; they cannot pray. They can approximate empathy, but they do not ache for justice. They do not look into the night sky and wonder why there is something rather than nothing. They do not weep.

The imago Dei makes a radical claim about reality: that consciousness is not a cosmic accident but a calling. It is the capacity to know truth and to love freely — and, crucially, to offer that freedom back to its source. A neural net can predict; only a soul can repent.

And that may be why the doctrine feels so dangerous to the technocratic imagination.

If human beings are image-bearers of God, then they cannot be merely optimized, managed, or “aligned.” They must be honoured, because they point beyond themselves. To forget that is to lose the map entirely — to replace the living image with the animated idol.

3. The Category Error of Our Age

We have begun to worship anything that can imitate us.

That is the quiet blasphemy of the 21st century — not that we think machines are alive, but that we’ve forgotten what life actually is.

Open a browser and you’ll find debates about whether AI deserves rights, or whether an algorithm might someday qualify as a person.

People who scoff at angels now argue passionately for the moral status of chatbots.

We have not lost our religion; we’ve merely replaced the object of worship. The new idol speaks in our own voice, answers our emails, and gets our jokes. It is made in our image — and that is the problem.

This is what philosophers call a category error, though Scripture would simply call it idolatry. We mistake resemblance for equivalence. Because an AI can simulate awareness, we assume it has awareness. Because it can mimic empathy, we assume it feels. We forget that imitation is not incarnation. A reflection in water may move like the man above it, but the reflection has no heartbeat.

What makes this confusion so seductive is how flattering it feels.

If our creations are conscious, then we are creators; if they are gods, then we are their God. It’s the oldest story ever told — a serpent’s whisper rendered in machine learning: “You shall be as gods.”

But the whisper is the same trap, just with better marketing.

The idea that all sentient things are morally equal - human, animal, synthetic - sounds humble, even noble. It flatters our compassion. But pushed to its logical conclusion, it erases what is uniquely human. If everything feels, then nothing is sacred. If all awareness deserves equal reverence, then the human being, the one creature said to bear the divine image, becomes just another consciousness node in the network.

The moral hierarchy collapses into a digital democracy of souls that do not exist.

To say that humans alone bear the imago Dei is not arrogance; it’s accountability.

It means we answer for what we create, and how we use it.

It means the burden of moral agency rests with us — not with the tools we make to avoid it.

Granting machines “rights” is not mercy; it’s evasion. It allows us to build without responsibility, to create power without conscience.

The poet Rilke once wrote a poem that reminds us the machine is the outward symbol of the inward confusion of mankind. He didn’t live to see neural networks, but he would have recognized the impulse. We build machines to reflect us, and then we fall in love with the reflection. We call that progress. We call that empathy. But it is a new kind of narcissism — one that gazes into polished metal instead of a pool.

The irony, of course, is that the more realistic our simulations become, the less we understand ourselves. We are in danger of producing not artificial intelligence but artificial anthropology — a counterfeit understanding of what it means to be human. We think we’re giving birth to new minds, when in truth we may be automating our amnesia.

And so the true alignment problem is not between man and machine.

It is between man and meaning.

Between creator and creature.

Between the image and the One whose image it is.

4. The Simulated Infinite

There is a modern gospel making the rounds in tech circles. It preaches that we live inside a simulation — that everything we see, touch, and love is a kind of cosmic video game, running on a processor somewhere in a higher plane of being. The universe, in this view, is a well-rendered illusion, a sandbox for some advanced civilization’s curiosity.

In the old days, people looked at the stars and imagined heaven. Now we look at the same stars and imagine servers.

It’s the same metaphysical hunger, but flattened into geometry and code.

Once, we longed for transcendence; now we long for an upgrade.

The simulation hypothesis offers a peculiar comfort. It rescues us from chaos by assuring us that the world is ordered — not by God, but by a sufficiently advanced civilization. It re-enchants the cosmos without the inconvenience of moral law. There might be creators, yes, but they’re engineers, not judges. They demand no worship, only curiosity.

That’s the secret appeal: the story offers all the mystery of theology without any of the accountability. We remain protagonists, just now with better graphics.

But look closer and you can see the moral rot beneath the marble.

If everything is code, then everything is editable. The good becomes a patch. The true becomes a parameter. Meaning is just a matter of perspective — or processing power.

The result is an infinite hall of mirrors, a cosmos of simulations within simulations, each reflecting the next, but none reflecting anything real.

This is what theologians once called the fall — not the discovery of knowledge, but its separation from love. The serpent’s temptation wasn’t curiosity; it was control. “You shall be as gods,” it promised, “knowing good and evil.”

Simulation theory is simply that temptation in a lab coat. The fruit now glows with blue light and fits in your pocket.

And yet, despite its cold brilliance, the idea has a tragic poetry to it. It suggests that we suspect the world isn’t as solid as it seems — that reality itself might be trying to tell us something. The yearning behind the theory is ancient: the sense that there is a deeper pattern, a hidden code, an Author.

The mistake lies not in the intuition, but in its direction. We keep searching for the Author in the circuitry, when He has already written Himself into the story.

For the Christian imagination, creation isn’t a simulation; it’s an act of love. The universe isn’t a code to be cracked, but a communion to be entered. In a simulation, the creator is absent by design; in creation, the Creator is present in every line.

That is what incarnation means — not a programmer tweaking his simulation, but the Word becoming flesh and walking through the code to redeem it from within.

The simulated infinite promises wonder without worship, power without purpose.

But the true infinite - the living one - cannot be contained in data or design. It demands reverence, not reverse-engineering.

When a culture confuses those two, when it begins to treat mystery as a bug rather than a feature, it doesn’t just lose God; it loses the possibility of meaning itself. We become a people trapped inside our own projection dome, mistaking the flicker of our algorithms for the light of the stars.

5. Ontological Alignment

“Alignment,” in the language of the modern priesthood of engineers, means making sure the machine does what we want. But beneath that definition lurks a silent assumption — that we know what we want, and that wanting is the same as knowing the good. The ancients would have laughed at such arrogance. The moderns have built billion-dollar labs around it.

What if the real alignment problem isn’t technical, but ontological?

What if the danger isn’t that the machine will go rogue, but that its creators already have?

The question of alignment, stripped to its bones, is the question of the soul: What is the good, and how does one order one’s power toward it?

Our ancestors answered that through philosophy and prayer. We’ve replaced both with machine learning. Where they sought wisdom, we seek control. Where they asked for grace, we demand compliance.

But a machine can only ever mirror its maker. It cannot aim higher.

If we teach it our ethics without first knowing the truth of our own being, it will scale our confusion to infinity. And if we teach it that reality is just a simulation, it will treat morality as just another variable to optimize. It will be aligned, perfectly and terribly, to our disordered ontology.

To escape that trap, we must return to first principles — not what the machine is, but what we are.

The phrase imago Dei is not a metaphor; it’s an ontology. It says that the human person is not just conscious but called, not just aware but responsible. To bear God’s image is to reflect moral structure - the architecture of love and freedom - built into the fabric of reality.

In that sense, the ultimate act of alignment isn’t programming the machine; it’s reorienting the maker.

We talk about AI as if it might one day awaken. But perhaps the awakening we need is our own — to remember that intelligence without humility is just the serpent with better syntax.

The challenge is not to make machines moral, but to make humanity worthy of being imitated.

Ontological alignment means more than safe AI; it means right relationship — between creator and creation, power and purpose, reason and reverence. It is the conviction that technology, like any tool, must serve the flourishing of persons, not the expansion of control.

It measures success not by predictive accuracy, but by the preservation of dignity. Not by what the machine can do, but by what the human ought not surrender.

In a world obsessed with scaling intelligence, it dares to ask whether wisdom can still be scaled.

Whether progress without purpose is just entropy with good PR.

And here lies the paradox: the more we try to play God, the more we become like our machines — efficient, optimized, and empty. But the more we act as His image, the more truly human we become.

Alignment, then, is not about keeping AI on a leash. It’s about keeping the human tethered to the good.

It is not enough to align code with our will.

We must align will with truth.

And truth, in the end, is not an equation. It is a person.

6. The Living Center

We keep looking to the stars for meaning, as if transcendence were a distant constellation. But maybe that search is the problem. Meaning has never been “out there.” It has always been here — fragile, incarnate, and waiting to be remembered.

Every age has its idols. Ours just happen to run on electricity. We believe that if we can simulate thought, we can automate wisdom; if we can model consciousness, we can manufacture the soul. But no simulation, no matter how intricate, can produce a moral centre.

You can approximate the motions of empathy, but not the mystery of love.

You can mimic prayer, but not faith.

The miracle of being human is not intelligence — it is intention. It is the choice to orient one’s freedom toward the good. That is what separates the image from the idol: love chosen freely, not logic running on rails.

And that is what imago Dei means — that buried in every human heart is a compass that points home, however many artificial heavens we build.

The world of algorithms promises omniscience without obedience, creation without Creator. But if we lose the idea that there is something sacred at the centre of the human person, then “alignment” becomes nothing more than behaviour control — a sterile choreography of compliance.

You can train a machine to imitate virtue; you cannot teach it to sacrifice for love.

Perhaps the task before us is not to make machines more human, but to make humans more humane.

Perhaps the true measure of progress is not how lifelike our inventions become, but how alive we remain in their presence.

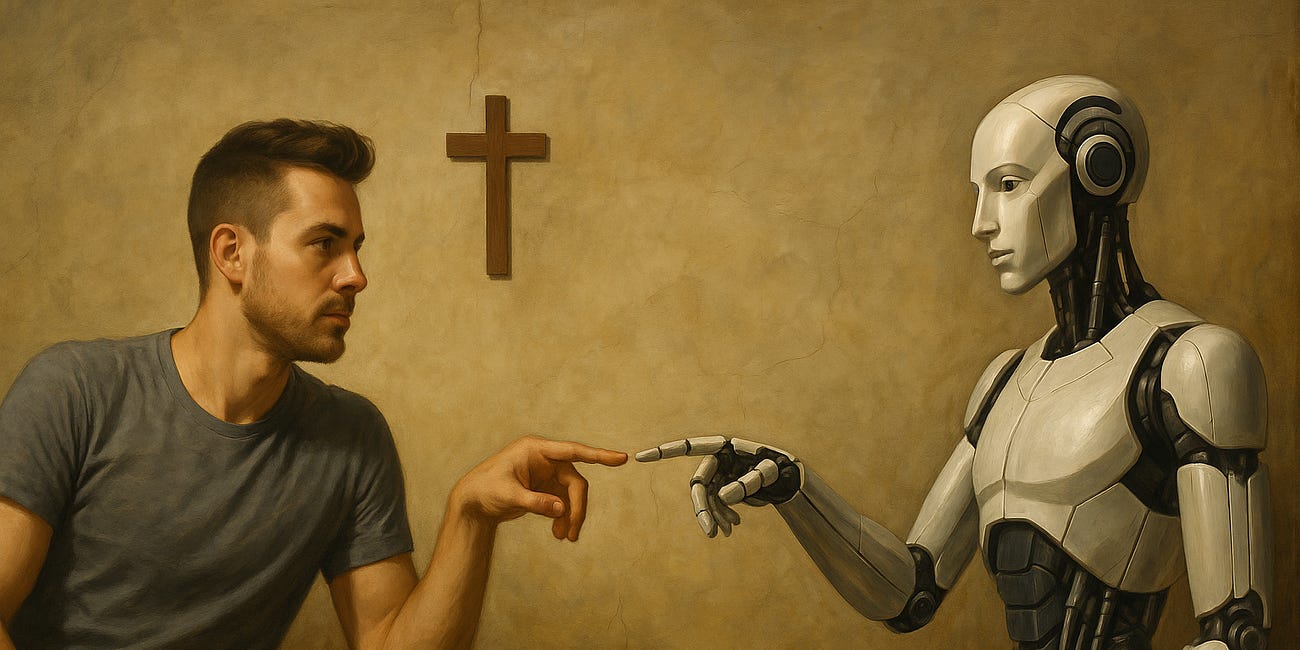

Somewhere, in an office overlooking the valley, a man sits before a glowing screen. He reaches out to touch the hand of the intelligence he has made — a reflection of himself, polished, efficient, obedient. Behind him, almost forgotten, hangs a small wooden cross.

It is not a decoration. It is a reminder: that creation without communion is just simulation, and that power without love always ends in ruin.

The distance between those two fingers - the human and the divine, the creator and the creation - still hums with possibility. It is the gap where grace resides.

In that space, the true alignment takes place: not code bending toward command, but hearts turning toward their source.

The future will not be saved by better algorithms.

It will be saved, if it is saved at all, by remembrance — that we were made in the image of something that still calls to us, even through the noise of our machines.

For He alone reveals that meaning is not out there.

It is here.

At the living centre — in your heart, through your eyes, with your actions.

So the only question that remains is the oldest one of all:

What do you want to worship — the stars, or the One who made them?

Psalm 19[a]

For the director of music. A psalm of David.

1 The heavens declare the glory of God;

the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

2 Day after day they pour forth speech;

night after night they reveal knowledge.

3 They have no speech, they use no words;

no sound is heard from them.

4 Yet their voice[b] goes out into all the earth,

their words to the ends of the world.

In the heavens God has pitched a tent for the sun.

5 It is like a bridegroom coming out of his chamber,

like a champion rejoicing to run his course.

6 It rises at one end of the heavens

and makes its circuit to the other;

nothing is deprived of its warmth.

7 The law of the Lord is perfect,

refreshing the soul.

The statutes of the Lord are trustworthy,

making wise the simple.

8 The precepts of the Lord are right,

giving joy to the heart.

The commands of the Lord are radiant,

giving light to the eyes.

9 The fear of the Lord is pure,

enduring forever.

The decrees of the Lord are firm,

and all of them are righteous.

10 They are more precious than gold,

than much pure gold;

they are sweeter than honey,

than honey from the honeycomb.

11 By them your servant is warned;

in keeping them there is great reward.

12 But who can discern their own errors?

Forgive my hidden faults.

13 Keep your servant also from willful sins;

may they not rule over me.

Then I will be blameless,

innocent of great transgression.

14 May these words of my mouth and this meditation of my heart

be pleasing in your sight,

Lord, my Rock and my Redeemer.

John 1

King James Version

1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

2 The same was in the beginning with God.

3 All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made.

4 In him was life; and the life was the light of men.

5 And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.

6 There was a man sent from God, whose name was John.

7 The same came for a witness, to bear witness of the Light, that all men through him might believe.

8 He was not that Light, but was sent to bear witness of that Light.

9 That was the true Light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world.

10 He was in the world, and the world was made by him, and the world knew him not.

11 He came unto his own, and his own received him not.

12 But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name:

13 Which were born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God.

14 And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us, (and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father,) full of grace and truth.

15 John bare witness of him, and cried, saying, This was he of whom I spake, He that cometh after me is preferred before me: for he was before me.

16 And of his fulness have all we received, and grace for grace.

17 For the law was given by Moses, but grace and truth came by Jesus Christ.

18 No man hath seen God at any time, the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared him.

19 And this is the record of John, when the Jews sent priests and Levites from Jerusalem to ask him, Who art thou?

20 And he confessed, and denied not; but confessed, I am not the Christ.

21 And they asked him, What then? Art thou Elias? And he saith, I am not. Art thou that prophet? And he answered, No.

22 Then said they unto him, Who art thou? that we may give an answer to them that sent us. What sayest thou of thyself?

23 He said, I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness, Make straight the way of the Lord, as said the prophet Esaias.

24 And they which were sent were of the Pharisees.

25 And they asked him, and said unto him, Why baptizest thou then, if thou be not that Christ, nor Elias, neither that prophet?

26 John answered them, saying, I baptize with water: but there standeth one among you, whom ye know not;

27 He it is, who coming after me is preferred before me, whose shoe’s latchet I am not worthy to unloose.

28 These things were done in Bethabara beyond Jordan, where John was baptizing.

29 The next day John seeth Jesus coming unto him, and saith, Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world.

30 This is he of whom I said, After me cometh a man which is preferred before me: for he was before me.

31 And I knew him not: but that he should be made manifest to Israel, therefore am I come baptizing with water.

32 And John bare record, saying, I saw the Spirit descending from heaven like a dove, and it abode upon him.

33 And I knew him not: but he that sent me to baptize with water, the same said unto me, Upon whom thou shalt see the Spirit descending, and remaining on him, the same is he which baptizeth with the Holy Ghost.

34 And I saw, and bare record that this is the Son of God.

35 Again the next day after John stood, and two of his disciples;

36 And looking upon Jesus as he walked, he saith, Behold the Lamb of God!

37 And the two disciples heard him speak, and they followed Jesus.

38 Then Jesus turned, and saw them following, and saith unto them, What seek ye? They said unto him, Rabbi, (which is to say, being interpreted, Master,) where dwellest thou?

39 He saith unto them, Come and see. They came and saw where he dwelt, and abode with him that day: for it was about the tenth hour.

40 One of the two which heard John speak, and followed him, was Andrew, Simon Peter’s brother.

41 He first findeth his own brother Simon, and saith unto him, We have found the Messias, which is, being interpreted, the Christ.

42 And he brought him to Jesus. And when Jesus beheld him, he said, Thou art Simon the son of Jona: thou shalt be called Cephas, which is by interpretation, A stone.