Beyond Alignment

A New Framework for Evaluating AI Thought-Leaders

Introduction

In recent weeks we’ve applied our emerging 10-axis analysis—blending G.K. Chesterton’s absolute-vs-relative moral lens, Aquinas’s Four Causes, and Marshall McLuhan’s media-as-message perspective—to two high-profile AI-alignment talks:

Emmett Shear (Co-founder of Twitch & SoftMax) on the “organic alignment” of humans and superintelligent AI.

Connor Leahy (Founder & CEO of Conjecture) on existential risk, algorithmic sociology, and the path to AGI/ASI.

Both thinkers are undeniably brilliant, but when viewed through these older, deeper frameworks, gaps and implicit “worships” emerge—patterns of reasoning they themselves neither acknowledge nor intend.

Our goal in this piece is not to condemn, but to highlight where even the sharpest AI advocates remain entangled in:

Materialist reverence for “emergent intelligence” (the Creation) over any transcendent moral ground (the Creator).

Unexamined moral premises (“What ought we to do?”) drawn purely from “what is,” rather than anchored in absolute goods.

Insufficient causal depth, missing the full sweep of why we value human freedom (Final Cause), how digital agents truly differ from living beings (Material & Formal Causes), and what “external agent” shapes their rise (Efficient Cause).

Above all, we’re planting a flag for a new school of AI critique—one that marries the rigour of classical Western thought with the nuance our digital era demands.

On Absolute vs. Relative Morality

Google A.I. overview

G.K. Chesterton, while not explicitly defining "two forms of morality" in a rigid, systematic way, often explored morality through contrasting perspectives. He frequently contrasted traditional, absolute morality with what he saw as the relativistic and often confused morality of his time, particularly in literature and social commentary.

Here's a breakdown of Chesterton's perspective:

Absolute vs. Relative Morality:

Chesterton frequently engaged with the concept of absolute morality, believing in objective truths and right and wrong, as opposed to the relativism that he saw as undermining traditional values. He often criticized modern literature, like Ibsen's plays, for confusing the reader about what is truly right or wrong.

Traditional Morality:

He championed traditional morality, rooted in Christian values and a belief in inherent human goodness. He saw this morality as a foundation for society and a source of meaning and purpose.

The "Negative Spirit" and Confusion:

Chesterton critiqued what he called the "negative spirit" in modern thought, which he associated with a focus on what is wrong or bad without a clear understanding of what is right. He believed this spirit could lead to moral confusion and a weakening of moral resolve.

The Importance of Tradition:

Chesterton saw tradition as a way of accessing wisdom from the past and as a safeguard against the excesses of individualistic thinking.

The Nature of Evil:

He believed that while there might be disagreement on what constitutes "good," there is a general agreement on what constitutes evil. However, people differ greatly on what evils they are willing to excuse or tolerate.

Morality and Art:

Chesterton believed that art, like morality, involves making choices and drawing lines. He saw both as essential for creating order and meaning.

In essence, Chesterton's exploration of morality involved a defence of traditional, absolute morality against what he perceived as the dangers of relativism and moral confusion in the modern world.

Example 1 - Depth of Comprehension - Logic vs. Logos

Here’s a perfect example of someone who fails to understand the point, not that I’m suggesting he’s a bad person. Clearly this is an attempt to make sense of a very challenging idea that ironically requires the very Chestertonian morality he’s trying to explain.

In the video “Nietzsche vs Chesterton – Ethics for Leaders,” Rick Walker opens by declaring Chesterton’s absolute morality to be “unchanging…consistent across all of the world’s great religions and Humanities and…across time.” On the surface, this sounds like a ringing defence of moral objectivity—but it, in fact, strips Chesterton’s insight of its crucial Christian foundation.

G.K. Chesterton insisted that true absolutes flow not from human consensus or mere tradition, but from a living Divine Authority whose revelation alone can anchor ethics in a transcendent good. To reduce his view to a generic “unchanging standard” shared by all religions misses both his critique of philosophical relativism and his conviction that human rights themselves derive from God, not from fallible human law. Whenever we look for an ethical foundation in anything less than the Christian Logos, Chesterton warned, we end up with shifting sands.

Below is Rick Walker’s opening—followed by a closer look at why its broad application of Chesterton’s quote in fact loses the plot in the very first thirty seconds.

“The great G.K. Chesterton told us that a moral standard must remain the same otherwise it is not really a standard…not only is it consistent across all of their world’s great religions and Humanities but is also consistent across time…”

Why this misses the mark

Chesterton was first and foremost a Christian apologist. His absolute morality springs from the eternal Logos revealed in Christ—no other system, he argued, can sustain the notion of an immutable good.

Human rights flow from God, not from paper statutes. When we sever ethics from a theistic ground, we inevitably lapse into relativism—exactly what Chesterton was fighting.

Not every religion or philosophy affirms the same inescapable moral claims. Chesterton’s point was that Christianity alone unites ethical universals with transcendence; to gloss it as a generic “same across all religions” robs his insight of its power.

Example 2 - Moral Absolutes vs. Relativism

Today’s debate about right and wrong isn’t really a tug-of-war between fascism and communism, but between moral absolutes and moral relativism. The Nuremberg Trials settled this: laws “above the law” must exist if we are to condemn atrocities regardless of orders or culture. Yet many contemporary thinkers, missing Chesterton’s insight into the West’s transcendent foundations, still drift toward relativism. A few—like Cliffe Knechtle—stand firm on that higher moral Rock, even when the storm of doubt rages.

Below is an excerpt from Knechtle’s “Moral Absolute vs. Moral Relativism,” in which he guides students to recognize that only a Mind beyond our own can ground the conscience that cries out, “Gassing Jews is absolutely wrong.”

Methods

Chesterton’s Absolute vs. Relative

Does the speaker appeal to timeless moral constants (life, dignity, truth) or slide into moral relativism (“freedom is highest good,” “whatever users want”)?

Aquinas’s Four Causes

Material: What “stuff” underlies their argument (data, silicon, “stories”)?

Formal: What conceptual schema or “grammar” frames their claims?

Efficient: Who or what agency drives their vision (markets, biology, self-telling memes)?

Final: What ultimate good (“order,” “flourishing,” “self-preservation”) do they serve?

McLuhan’s Media-as-Message

How does the form of their talk (stories about alignment, metaphors of biology, network analogies) shape what they leave unsaid?

New 10-Axis Matrix

Epistemic Integrity

Logical Coherence

Presuppositional Clarity

Moral Grounding

Teleological Vision

Mechanistic Transparency

Social Efficacy

Personal Resonance

Subjective Wisdom

Agentive Integrity

With these adjustments:

Presuppositional Clarity surfaces the unspoken lens each speaker uses.

Teleological Vision and Mechanistic Transparency split “Causal Depth” into “why” and “how.”

Moral Grounding flags absolute vs. relative ethics.

Agentive Integrity checks for true freedom vs. soft totalitarianism by algorithm.

We score and compare each talk along these axes, then surface where both converge in the same blind spot—a de facto “cult of emergence” that never names the Creator.

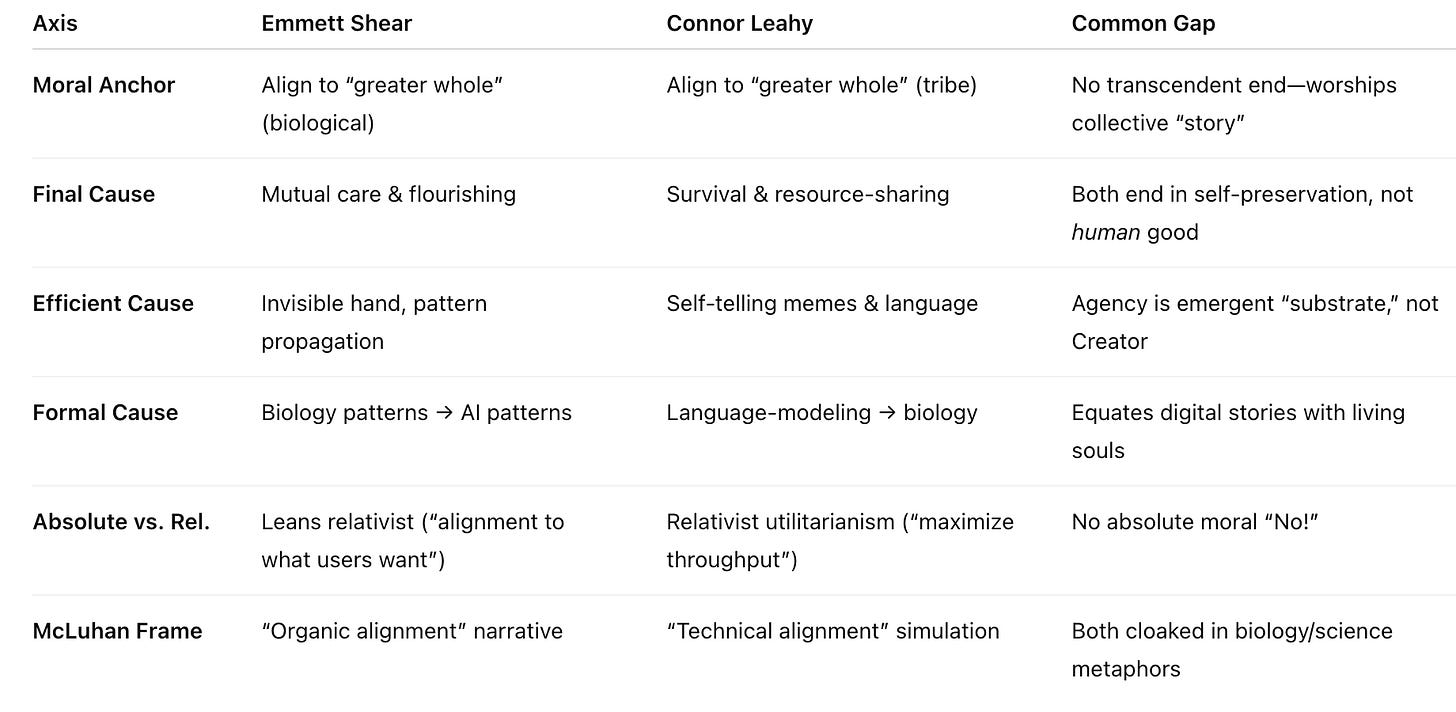

Analysis (Highlights)

From Shear we inherit a panentheistic AI cult, viewing alignment as a biological imperative rather than an ethical choice. From Leahy we inherit an agnostic utilitarianism, extracting “ought” exclusively from “is” and building no refuge for free will or human dignity when the chips come down.

Proposal: A “Logos-Informed” AI Critique

We need a hybrid methodology that:

Reclaims the Final Cause: Anchor our AI goals in inviolable goods—human dignity, agency, truth, and beauty—before tuning “loss functions.”

Names the Creator: Recognize that emergent patterns arise through us, but do not replace the transcendent ground of moral law.

Unfolds the Four Causes: Systematically map digital agents alongside living beings to see where their formal structures and efficiencies diverge.

Insists on Absolute “Nos”: Even in a workshop on “organic alignment,” we must be able to say: “No, there are certain rights and boundaries that cannot be optimized away.”

Marries McLuhan & Thomism: Decode how the medium of our AI talk shapes what we think we can or cannot ask, then reclaim the grammar of Christian intellectual tradition to ask it.

Call for Collaborators

If you’ve ever felt that neither Silicon Valley hype nor academic AI ethics capture the full moral gravity of the challenge, join us. We’re building:

A living “Logos-Informed AI” curriculum, pairing Plato’s cave, Chesterton’s orthodoxy, and Aquinas’s syllogisms with modern case studies from DeepMind to Anthropic.

A public rubric (open-source) to score any AI-alignment talk across these “10 axes of transcendence.”

A community of autodidacts committed to teaching, testing, and refining this framework in real time—through workshops, Substack essays, podcasts, and code.

🤝 Reply here or reach me at andrewdjcorner@gmail.com (to be updated) to help draft the first full-length “Logos AI Glossary” or pilot our rubric in your local meetup.

Why this matters:

Without a moral bedrock, we’ll ride the next AI wave straight into a horizonless “cult of emergence,” where silicon patterns worship themselves—and billions of human souls go uncounted. Let’s anchor AI in truth that stands outside the algorithm, before the machines write us out of our own story.